How To Eat An Egg In A Rebounding Rwanda

By Patricia Crisafulli & Andrea Redmond In a rural preschool at Rugarama in northern Rwanda, some two hours north of the capital city of Kigali, 90 or so three- to six-year-olds sit patiently on a grassy patch outside a crumbling one-room schoolhouse with only gaps where windows and the door should be. Having sung, prayed, counted, and chanted the days of the week and months of the year in their native Kinyarwanda and English (fluency in which is a national education goal), the children wait for the highlight of the day: a hard-boiled egg.]]>

How To Eat An Egg In A Rebounding Rwanda

By Patricia Crisafulli & Andrea Redmond

In a rural preschool at Rugarama in northern Rwanda, some two hours north of the capital city of Kigali, 90 or so three- to six-year-olds sit patiently on a grassy patch outside a crumbling one-room schoolhouse with only gaps where windows and the door should be. Having sung, prayed, counted, and chanted the days of the week and months of the year in their native Kinyarwanda and English (fluency in which is a national education goal), the children wait for the highlight of the day: a hard-boiled egg.

In a rural preschool at Rugarama in northern Rwanda, some two hours north of the capital city of Kigali, 90 or so three- to six-year-olds sit patiently on a grassy patch outside a crumbling one-room schoolhouse with only gaps where windows and the door should be. Having sung, prayed, counted, and chanted the days of the week and months of the year in their native Kinyarwanda and English (fluency in which is a national education goal), the children wait for the highlight of the day: a hard-boiled egg.

Firm taps of the shells against a ridge of rock produce a crack. Then the peeling begins. Some children take a bite as soon as the top is uncovered and then continue removing the rest of the shell. Others wait until the egg fully emerges. No one gobbles or grabs. Older children help younger ones. One little girl nibbles the white first and then savors the round ball of cooked yolk.

The eggs are no mere mid-morning snack. They provide an infusion of protein at a critical juncture in child development, particularly for these needy rural children. Even when there are sufficient calories in their diet, protein is often deficient, which can impair body and brain development. Eggs are a perfectly portable protein source with ample shelf-life, even at room temperature, and contain the right balance of amino acids for human consumption.

Distribution of eggs to rural Rwandan preschoolers in the country’s Northern Province is the work of a U.S.-based nongovernmental organization (NGO) called One Egg, working with Rwandan and stateside partners. On the ground in Rwanda, One Egg collaborates with the Anglican Shyira Diocese, which currently operates 217 child development centers, with plans to expand to 325. Of the 217, 15 of these preschools currently receive eggs—a number One Egg hopes will grow steadily through stateside donor support.

The eggs are procured by One Egg from a poultry farm outside Musanze, the largest city in the Northern Province, which is operated by Ikiraro Investments, a Rwandan corporation with backing from American social entrepreneur Tom Phillips, as well as technical support from poultry giant Tyson Foods TSN -0.07% and its Cobb-Vantress research and technology arm.

Significantly, there is no government money here and no foreign aid. Instead, there is the transfer of technology, know-how, and best practices at the poultry farm. The eggs, therefore, reflect the importance of eschewing traditional aid and handouts in favor of empowering partnerships that pursue good works aligned with the Rwandan government’s priorities for development, especially at the lowest socioeconomic tier. As we wrote in our book, Rwanda, Inc., the emphasis is on development that is pro-poor, as evidenced in the 1 million Rwandans raised from poverty between 2006 and 2011.

Admittedly, progress in Rwanda, which is in the midst of a strong comeback since the 1994 genocide—with milestones such as 8% GDP growth, universal health care, 12 years of compulsory education, and the expectation that it will meet virtually all its United Nations Millennium Development Goals by 2015—starts at square one with incremental gains. The same can be said for the Shyira Diocese’s child development centers, where there is far more need than the means to deliver eggs. A harsh example is at Mugera on the Ugandan border where a mud-brick schoolhouse with a dirt floor is accessible only by a narrow rutted track that could never be called a road. There, children recite the same songs, prayers, and vocabulary lessons as at Rugarama, but there is no egg feast at the end.

As for those without egg deliveries as yet, the centers themselves, no matter how humble, are at least a start toward attaining the diocese’s four-fold goals, as explained by Bishop Laurent Mbanda: child security, with a safe environment for young children whose mothers work the fields; education, including an introduction to basic English; spiritual development; and nutrition.

Although the need is great, it cannot overshadow what is happening now: the diets of 1,500 rural preschoolers are supplemented with protein. Even anecdotally, children who receive the eggs show signs of physical and cognitive gains.

The intention is strong and the partners are committed to tackle poverty, nutrition, and child development issues among Rwanda’s poor—with more brown-shelled eggs, hard boiled over a wood fire at a rural preschool, resting in the palm of a child’s hand.

]]> President Paul Kagame of Rwanda at the 2010 Tribeca Film Festival.

(Photo credit: Wikipedia)[/caption]

President Paul Kagame of Rwanda at the 2010 Tribeca Film Festival.

(Photo credit: Wikipedia)[/caption]

By Andrea Redmond & Patricia Crisafulli

Amid the rhetoric, pro and con, around Rwanda, the impartial voice of the marketplace has spoken, with a ringing endorsement of its economic turnaround and prospects for continued growth.

Last week, Rwanda’s debut on the global bond market raised $400 million with an offering that was heavily over-subscribed by nearly eight times. Final yield on the 10-year bonds of 6.875% was less than reported expectations in the low-7% area, due to strong buyer interest. Proceeds will go to repayment of bank loans, infrastructure such as a hydropower project, expansion of the national airline RwandAir, and the completion of a convention center in the capital of Kigali.

The successful bond issue triggered a flurry of enthusiastic postings on Twitter from Rwandan government officials (very savvy users of social media). Finance Minister Claver Gatete hailed a “great day for Rwanda after the investors have shown confidence in our economy….” President Paul Kagame tweeted his congratulations to those who worked to bring the bond offering to a successful conclusion, adding “Let’s continue forward.”

Beyond Rwanda’s enthusiasm, what speaks even more loudly is the oversubscription for these bonds. Yes, there is interest these days in higher yields and geographic diversification. But specific to Rwanda, the success of this offering shows widespread recognition that what has happened to transform this country socially, economically, and politically is real and sustainable.

Rwanda truly is the ultimate turnaround. For the African nation, the comeback has been from the depths of human bankruptcy: genocide in 1994 in which 1 million people were killed in 100 days. Since then, the rebuilding has been impressive, with GDP growth that has risen by 7-8% annually in recent years. In 2012, GDP per capita grew to US$644, up from $593 a year before, according to Rwandan government figures.

Fitch, which affirmed a “B” rating on Rwanda, noted its “solid economic policies and a track record of structural reforms, macroeconomic stability, and low government debt” (23.3% of GDP in Rwanda, compared to the median of 43.5% among B-rated peers). Certainly, the country is not without its challenges; it is landlocked, which vastly increases transportation costs for imported goods, and more electrical generation capacity is needed. It is often clouded by geopolitics, most notably the morass of conflict in the neighboring Democratic Republic of the Congo (DRC). Kagame draws criticism for being too tightly controlling, and human rights watchers charge the country suppresses political opposition and free speech.

Rwanda, post-genocide, remains a complex place. Having the perpetually turbulent DRC as a next-door neighbor (where some masterminds of the genocide have sought refuge) complicates matters. Yet the country, backed by the strength of its leaders, has clearly put itself on a path of revival and renewal based upon values such as one Rwanda for all Rwandans. It offers universal health care and 12 years of compulsory education for all children, has made significant gains in poverty reduction and food security, and seeks to foster private sector development though homegrown entrepreneurship and foreign direct investment.

Rwanda, post-genocide, remains a complex place. Having the perpetually turbulent DRC as a next-door neighbor (where some masterminds of the genocide have sought refuge) complicates matters. Yet the country, backed by the strength of its leaders, has clearly put itself on a path of revival and renewal based upon values such as one Rwanda for all Rwandans. It offers universal health care and 12 years of compulsory education for all children, has made significant gains in poverty reduction and food security, and seeks to foster private sector development though homegrown entrepreneurship and foreign direct investment.

As we wrote in Rwanda, Inc., the country is no Garden of Eden for business investment. The wheels turn slowly at times with extra bureaucracy—the unintended consequence of strictly enforced zero tolerance for corruption, a policy that is a huge positive for business—and there is need for human capital development, particularly at the middle tier. But Rwanda’s progress continues apace, which the marketplace, the impartial arbiter, recognizes.

Andrea Redmond and Patricia Crisafulli are co-authors of “Rwanda, Inc.: How a Devastated Nation Became an Economic Model for the Developing World” (Palgrave-Macmillan, 2012).

]]>Rwanda: A Stunning Turnaround On A Continent Marked By Broken Promises

2/12/2013 By Patricia Crisafulli and Andrea Redmond At a recent gathering of business and political leaders in Kigali, President Paul Kagame, the charismatic yet controversial Rwandan leader, stated, “We have understood for a long time that you can’t cure poverty without democracy. The only cure is through business, entrepreneurship, and innovation.” His pro-business and free-market comments are the moral of the story of the “other Rwanda,” the one that has moved beyond what it is perhaps best known for—the 1994 genocide in which one million people were killed in 100 days. And, it contrasts with the current crossfire of accusations (vehemently denied by the Rwandan government) of alleged support to a rebel group in its chronically violent next-door neighbor, the Democratic Republic of the Congo.]]>

At a recent gathering of business and political leaders in Kigali, President Paul Kagame, the charismatic yet controversial Rwandan leader, stated, “We have understood for a long time that you can’t cure poverty without democracy. The only cure is through business, entrepreneurship, and innovation.” His pro-business and free-market comments are the moral of the story of the “other Rwanda,” the one that has moved beyond what it is perhaps best known for—the 1994 genocide in which one million people were killed in 100 days. And, it contrasts with the current crossfire of accusations (vehemently denied by the Rwandan government) of alleged support to a rebel group in its chronically violent next-door neighbor, the Democratic Republic of the Congo.]]>Rwanda: A Stunning Turnaround On A Continent Marked By Broken Promises

2/12/2013

By Patricia Crisafulli and Andrea Redmond

At a recent gathering of business and political leaders in Kigali, President Paul Kagame, the charismatic yet controversial Rwandan leader, stated, “We have understood for a long time that you can’t cure poverty without democracy. The only cure is through business, entrepreneurship, and innovation.” His pro-business and free-market comments are the moral of the story of the “other Rwanda,” the one that has moved beyond what it is perhaps best known for—the 1994 genocide in which one million people were killed in 100 days. And, it contrasts with the current crossfire of accusations (vehemently denied by the Rwandan government) of alleged support to a rebel group in its chronically violent next-door neighbor, the Democratic Republic of the Congo.

Within Rwanda, another narrative continues to unfold, with a positive impact that could extend well beyond its borders: the slow, steady, and consistent promotion of entrepreneurship and private sector development, two powerful ingredients in the progress toward full democracy in this landlocked country of 11 million people.

According to the World Bank’s Doing Business 2013 report, Rwanda ranks 52 out of 185 on “ease of doing business” and 8 on “ease in starting a business.” It is the second most improved nation globally and the top improved in sub-Saharan Africa since 2005. Through safety and security, zero-tolerance for corruption, and a stated goal to eliminate foreign aid (currently about 40 percent of its budget), Rwanda has put itself on a trajectory toward greater self-sufficiency; the evidence is in the numbers—projected 7.8% GDP growth in 2013, making it the ninth fastest growing economy in the world.

Foreign direct investors include Visa Inc., with its year-old cashless banking and payment processing ventures, and ContourGlobal, a New York-based company installing technology to extract methane gas from the waters of Lake Kivu to generate electricity. Chinese construction, South African telephony, and soon an Israeli solar-power venture are but some of the multinational involvements. Carnegie Mellon’s new Rwandan campus offers a master of science degree in information technology, reflecting Rwanda’s vision of evolving into an IT-based economy.On a return trip to Rwanda last week, we saw ample evidence in Kigali: a new and fully-leased 20-story skyscraper, tower cranes that punctuate the skyline, and shiny metal roofs in rural areas that attest to growing household income. (Rwanda raised one million people out of poverty between 2006 and 2011.) Agricultural cooperatives improve efficiency and productivity. Coffee washing stations produce value-added “fully washed” coffee beans stripped of their outer hull and mucilage for export to the U.S., Europe, and Asia.

Yet most impressive are the more modest homegrown ventures: new boutique hotels, restaurants, small IT shops, printers, event planning, and tourism offerings. (In 2010 alone, 18,447 new businesses were registered in Rwanda.) A young woman dressed in smart attire urged two visitors to come to her new shop, which sells upscale fabrics and offers custom tailoring. The nascent Rwanda Stock Exchange lists four stocks—two Rwandan and two cross-listings—along with a few bonds, and plans to expand from truncated open-outcry sessions (which with a handful of brokers and light volume are more murmur than roar) to an electronic platform.

While hardly the next Facebook or Google, this is the kind of entrepreneurship that’s needed in Rwanda, where the average age is just under 20. Twelve years of compulsory education, increased enrollment in institutions of higher learning, and more vocational training will produce a generation of workers who cannot possibly be employed by the government. On a continent in which power tends to coagulate at the top and rarely spreads to regional and local levels, Rwanda preaches a gospel of free enterprise and private sector job creation.

Rwanda is not without its challenges and criticisms; among them are human capital development, particularly at the mid-tier level, and bureaucracy and chronic delays that are the unintended consequences of the drive to prevent corruption. (Paralysis can set in when something should, legitimately, be expedited, out of fear of even the appearance of impropriety.) Politically, Rwanda needs further gains in free speech (critics charge it silences political opposition) and more freedom for local press that must professionalize.

But Rwanda has come very far, very fast, from the lowest level of human-induced catastrophe that left it morally, socially, politically, and financially bankrupt. Out of those ashes of the 1994 genocide, when the West did nothing to intervene, Rwanda learned not to depend long-term on the outside world for help (a lesson that should be heeded in Haiti, where despite billions in aid, virtually no material gains have been made).

As Rwanda receives help from the likes of the Clinton Foundation, Partners In Health, Tony Blair’s Africa Governance Initiative, and many others, its appetite is for knowledge and development of institutions, not hand-outs that come with someone else’s agenda attached.

If Rwanda does, indeed, develop entrepreneurship and free enterprise as tools to build a future of its own design, its success will provide a stunning example of “the ultimate turnaround” on a continent in which there have been far too many examples of broken promises and unrealized potential.

Patricia Crisafulli and Andrea Redmond are authors of Rwanda, Inc.: How a Devastated Nation Became an Economic Model for the Developing World (November 2012, Palgrave-Macmillan).

]]>

]]>

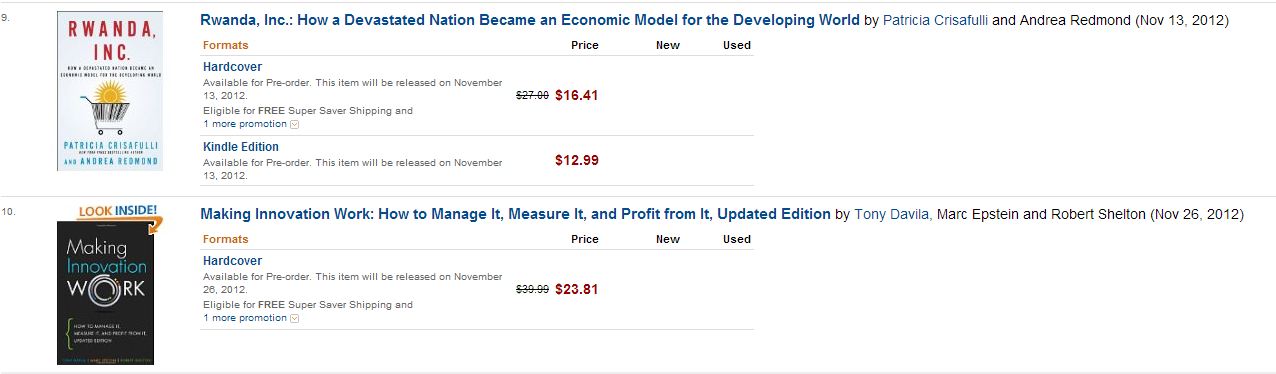

]]>RWANDA, INC. by Patricia Crisafulli and Andrea Redmond hits No. 9 on the Amazon Best Business Book list for November, and will officially be on sale on November 13th.

]]>Rwanda, Inc.: How a Devastated Nation Became an Economic Model for the Developing World

by Patricia Crisafulli and Andrea Redmond

“In Rwanda, Inc., Crisafulli and Redmond recount the rise of an unyielding people and their chief executive, President Paul Kagame. The Rwandans, rallying around their national pride, have built predictable systems that reward enterprise and hard work, and created an exceptional blueprint for other developing countries.”—President Bill Clinton

“Andrea Redmond and Patricia Crisafulli are known for their ability to connect with people, examine leadership skills and teach us through their compelling observations and insights. As advocates for the future of Rwanda, they are now telling a story that we can all benefit from hearing.”–Jamie Dimon, Chairman and CEO, JPMorgan Chase

]]> In their latest, Crisafulli and Redmond (coauthors of Comebacks: Powerful Lessons from Leaders Who Endured Setbacks and Recaptured Success on Their Terms) investigate the Rwandan renaissance, focusing on “Rwanda’s CEO,” Paul Kagame, a former refugee turned politician. Now in his second term as president, Kagame looks toward the future in light of the “lofty” objectives he set for his administration and nation. His hope to make Rwanda a self-sufficient economy is encompassed in his Vision 2020, a series of goals that range from decreasing the number of citizens who live in poverty to developing the Rwandan stock market. During Kagame’s tenure, he has placed a heightened importance on education–making 12 years of schooling compulsory– while stimulating agriculture. His initiatives favoring universal health care, unification and reconciliation, and grassroots change have improved the quality of life and encouraged investment by outsiders. Although the authors seem too quick to dismiss criticism by Human Rights Watch and others, this is a fascinating portrait of a nation and a president at a pivotal moment in history. Agent: Delia Berrigan Fakis, DSM Literary Agency. (Nov.)

In their latest, Crisafulli and Redmond (coauthors of Comebacks: Powerful Lessons from Leaders Who Endured Setbacks and Recaptured Success on Their Terms) investigate the Rwandan renaissance, focusing on “Rwanda’s CEO,” Paul Kagame, a former refugee turned politician. Now in his second term as president, Kagame looks toward the future in light of the “lofty” objectives he set for his administration and nation. His hope to make Rwanda a self-sufficient economy is encompassed in his Vision 2020, a series of goals that range from decreasing the number of citizens who live in poverty to developing the Rwandan stock market. During Kagame’s tenure, he has placed a heightened importance on education–making 12 years of schooling compulsory– while stimulating agriculture. His initiatives favoring universal health care, unification and reconciliation, and grassroots change have improved the quality of life and encouraged investment by outsiders. Although the authors seem too quick to dismiss criticism by Human Rights Watch and others, this is a fascinating portrait of a nation and a president at a pivotal moment in history. Agent: Delia Berrigan Fakis, DSM Literary Agency. (Nov.)

Reviewed on: 08/27/2012

]]>

DSM Agency authors Patricia Crisafulli and Andrea Redmond have written an article on a well-regarded Wall Street program that was recently brought to Rwanda. You can read the entire article here.

RWANDA, INC. by Crisafulli and Redmond will be published in the fall by Palgrave-Macmillian.

As seen on Las Vegas Review-Journal:

February 19, 2012

John P. Strelecky, DSM Agency author of THE WHY CAFE, explains that employers look for “someone who approaches them with an idea of a new position, as long as it makes sense.”

Read the full article here.

]]>